N-Body in Unity With Threads

This model will extend from our previous example using TimestepModel. We will build a class that uses a threaded update method, like before, and will use that update method to integrate forward a system of orindary differential equations.

Our simple example showed performance gains by separating out the computation from the Unity scene loop, but how will a more complicated problem behave?

Let’s build something that will require a great deal more work per step. This example will walk through implementing a solution and visualization of the gravitational N-Body problem.

The gravitational N-Body problem describes the behavior of objects in space attracted to each other via gravity. Each object will feel a force of

\[\vec{F}_i = \sum_j{G \frac{m_i m_j}{r_{ij}^2} \frac{\vec{r}_{ij}}{r_{ij}}}\]where

\[\vec{r}_{ij} = \vec{r}_j-\vec{r}_i\]and

\[r_{ij} = |\vec{r}_{ij}|\]For simplicity, we’re going to use a unit system in our simulation such that $G=1$, each mass is equal and $\sum{m_i}=M=1$, and all of our objects start off in a space roughly 1 unit around the origin.

(As an aside, scaling your units helps to keep your numbers at an order of magnitude near unity, which is good for preventing overflow and underflow errors in your computation, and keeps your scene sizes closer to typical in your Unity visualization. The easiest way to scale the gravitational N-Body problem is to set a value of G that matches the other units you want to use. If you want to use specific values in your own choice of units, the easiest thing to do is figure out what $G$ is in your unit system. Since G is typically given in SI, just figure out your units in SI values, and then \(G_{scaled}=6.6740831e-11 UnitMass_{SI} UnitTime^2_{SI} UnitLength^{-3}_{SI}\) .)

Our overall process will be to create an empty GameObject in our scene, and attach a script to it called Model that will extend TimestepModel. We will create and initialize an array of values for the positions and velocities of all of our objects. We will create a second script that extends Integrator called NBody. In this script, we will create a RatesOfChange routine that implements the forces listed above. In Model, we will have a member variable of type NBody. Model’s TakeStep method will have our member variable of type NBody call the RK4Step method. In Model, we will create a spherical game object via scripting for each body, and in Model’s update routine, we will at each screen update the position of each sphere to the corresponding coordinates of each body in the calculation.

Start by creating a new 3D Unity project, and add in the Unity Modeling Toolkit package, or copy TimestepModel.cs and Integrator.cs from previous blog posts.

Add a empty GameObject in the scene, and name it Model. Add a “New Script” component to Model, also called Model. Save your scene.

Open Model.cs and change the class definition to extend TimestepModel instead of MonoBehaviour. Implement an empty TakeStep routine.

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class Model : TimestepModel {

public override void TakeStep (float dt) {

}

// Use this for initialization

void Start () {

}

// Update is called once per frame

void Update () {

}

}

Let’s also create a new C# script in the project panel, not attached to any object, called NBody. Open this, delete the Update and Start methods, and change the extend keyword to extend from Integrator. Add in an empty RatesOfChange override method.

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class NBody : Integrator {

public override void RatesOfChange (double[] x, double[] xdot, double t)

{

}

}

The NBody model will need a few member variables to describe our problem, such as the number of objects, and the parameters of the system. Also, let’s create a routine to place the setting of initial conditions and to create an array $x$ for the state variables.

Note that we have 6 equations for each 1 body. This is because the state of a single body includes $\vec{r} = (x,y,z)$ and $\vec{v} = (v_x, v_y,v_z)$.

Our initial conditions will be random positions and velocities, and the total mass will be evenly divided over the bodies.

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class NBody : Integrator {

int nBodies;

double M;

double G;

public double [] x; // public for easy access from Model

double [] m;

public void setIC(int nBodies, double M, double G) {

this.nBodies = nBodies;

this.M = M;

this.G = G;

x = new double[6 * nBodies]; // create state variables

m = new double[nBodies];

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

m [i] = M / nBodies;

x [i * 6 + 0] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 1] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 2] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 3] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 4] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 5] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

}

Init (6 * nBodies); // allocate Integrator work arrays

}

public override void RatesOfChange (double[] x, double[] xdot, double t)

{

}

}

For the rates of change, we want to populate the array xdot with values of $\dot{x}$, $dot{y}$, $dot{z}$, $dot{v}_x$, $\dot{v}_y$, and $\dot{v}_z$, and to do this for every object–so the arrays x and xdot are both $6 \times nBodies$ long. We could arrange the arrays in one of two ways, we could have all the information for one body in a block of data 6 numbers long, or we could have all of the x values for every object in one block, all of the y values in one block, etc. It’s more likely that for a given computation I need to know everything about an object than it is for me to suddenly need to know all of my x components without y and z, so keeping all of an objects information close together is better for memory efficiency. (Memory gets pulled into cache on the CPU in blocks, so if the second piece of information you need is near the first in memory, it’s already in cache and thus is accessed faster.)

To index our arrays, then, we will use the index $[i*6+j]$ to access the jth component (0-5 for x,y,z,vx,vy,vz respectively) of the ith object.

The first step in setting the rates of change will be to set $\dot{\vec{x}}$. This is, by definition, just $\vec{v}$, which is part of our state variables already, so we can just use the current value of $v$ to set $\dot{x}$.

Next, we need to set the accelerations, $\dot{v}$. This will be done one force at a time in summative fashion, so begin by zeroing out all of the accelerations. Then, we will loop over all of the possible interactions between objects, and use the fact that forces are equal and opposite to set the acceleration term for each object affected by each force.

Note that our force terms as vectors all contained the term

\[\frac{\vec{r}_j - \vec{r}_i}{|\vec{r}_j - \vec{r}_i|}\]If $\Delta x = x_j - x_i$, $\Delta y = y_j - y_i$, and $\Delta z = z_j - z_i$, then we can write $\Delta r = \sqrt{\Delta x^2 + \Delta y^2 + \Delta z^2}$. With that,

\[\frac{\vec{r}_j - \vec{r}_i}{|\vec{r}_j - \vec{r}_i|} = \frac{\Delta x}{r}\hat{i} + \frac{\Delta y}{r}\hat{j} +\frac{\Delta z}{r}\hat{k}\]This makes the calculation and computation of the vector terms of the acceleration very straightforward.

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class NBody : Integrator {

int nBodies;

double M;

double G;

public double [] x; // public for easy access from Model

double [] m;

public void setIC(int nBodies, double M, double G) {

this.nBodies = nBodies;

this.M = M;

this.G = G;

x = new double[6 * nBodies]; // create state variables

m = new double[nBodies];

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

m [i] = M / nBodies;

x [i * 6 + 0] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 1] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 2] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 3] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 4] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 5] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

}

Init (6 * nBodies); // allocate Integrator work arrays

}

public override void RatesOfChange (double[] x, double[] xdot, double t)

{

// set xdot

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

xdot [i * 6 + 0] = x [i * 6 + 3];

xdot [i * 6 + 1] = x [i * 6 + 4];

xdot [i * 6 + 2] = x [i * 6 + 5];

}

// zero out vdot

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

xdot [i * 6 + 3] = 0;

xdot [i * 6 + 4] = 0;

xdot [i * 6 + 5] = 0;

}

// force terms

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

for (int j = i + 1; j < nBodies; j++) {

double dx = x [j * 6 + 0] - x [i * 6 + 0];

double dy = x [j * 6 + 1] - x [i * 6 + 1];

double dz = x [j * 6 + 2] - x [i * 6 + 2];

double dr2 = dx * dx + dy * dy + dz * dz;

double dr = System.Math.Sqrt (dr2);

xdot [i * 6 + 3] += G * m [j] / dr2 * dx / dr;

xdot [i * 6 + 4] += G * m [j] / dr2 * dy / dr;

xdot [i * 6 + 5] += G * m [j] / dr2 * dz / dr;

xdot [j * 6 + 3] -= G * m [i] / dr2 * dx / dr;

xdot [j * 6 + 4] -= G * m [i] / dr2 * dy / dr;

xdot [j * 6 + 5] -= G * m [i] / dr2 * dz / dr;

}

}

}

}

There are some efficiency improvements we could make in the loop structure here, though they might run the risk of hurting readability for the purposes of this example.

With this, we can add in some control to run this calculation in Model, and connect it to a visualization.

In Model, let’s create a member variable of type NBody called nBody, run setIC, and set up the step routines in TakeStep.

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class Model : TimestepModel {

public float G = 1;

public float M = 1;

public int nBodies = 10;

NBody nBody;

public override void TakeStep (float dt) {

nBody.RK4Step (nBody.x, modelT, dt);

}

// Use this for initialization

void Start () {

nBody = new NBody ();

nBody.setIC (nBodies, M, G);

ModelStart ();

}

// Update is called once per frame

void Update () {

}

}

We’ve got everything except the visualization. If you wanted to test at this point, you might add a Debug.Log() statement in Model.Update.

To add in a visualization, we could create a prefab gameobject for the visual for each body, Instantiate a bunch of them in Model.Start, and position them to catch up with the threaded model in Model.Update.

Create a sphere in your scene’s Hierarchy panel. Name it Body. Drag it into Project->Assets to make a prefab. Delete it from your scene.

Highlight the prefab body. Remove the collider component in the inspector panel.

In Model, add a public member variable of type GameObject. Name it bodyPRE. Save Model.cs, go back to the scene, and drag your prefab into the now open spot in the inspector window when Model is selected in the scene. Also create an array of gameobjects in the member variables called bodies.

In Model.Start, let’s add a new instance of bodyPRE for every object, and store them in bodies. In Update, set transform.position of each element of bodies.

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class Model : TimestepModel {

public float G = 1;

public float M = 10;

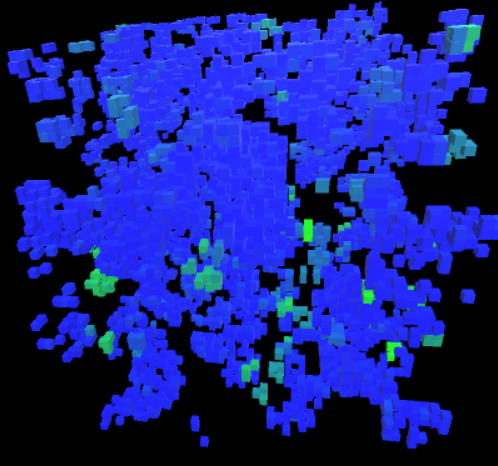

public int nBodies = 1000;

NBody nBody;

public GameObject bodyPRE;

GameObject [] bodies;

public override void TakeStep (float dt) {

nBody.RK4Step (nBody.x, modelT, dt);

}

// Use this for initialization

void Start () {

nBody = new NBody ();

nBody.setIC (nBodies, M, G);

ModelStart ();

bodies = new GameObject[nBodies];

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

bodies [i] = Instantiate (bodyPRE);

}

}

// Update is called once per frame

void Update () {

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

Vector3 newPos = new Vector3 (

(float)nBody.x [i * 6 + 0],

(float)nBody.x [i * 6 + 1],

(float)nBody.x [i * 6 + 2]);

bodies [i].transform.position = newPos;

}

}

}

You may find you want to drop the value of ModelDT, or change the mass, or number of objects. For a large number of objects, it is very likely the spheres being drawn are too big, and you can select the prefab and change its scale in x, y, and z to accommodate this.

Running at DT = 0.01, M=10, and NBodies = 100 (be sure to set in the editor, not in the code, as editor can override public variables!), we get a high number of ejections from the system due to close encounters. Many of these close encounters are in fact numerical artifacts due to a discrete stepping algorithm.

Let’s add a softening factor to our calculation, and link it up to the GUI.

In NBody, add a member variable “soft” to the class, and add “soft*soft” to the value of dr2 in RatesOfChange. In setIC, allow a value to be passed to set soft.

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class NBody : Integrator {

int nBodies;

double M;

double G;

public double [] x; // public for easy access from Model

double [] m;

double soft;

public void setIC(int nBodies, double M, double G, double soft) {

this.nBodies = nBodies;

this.M = M;

this.G = G;

this.soft = soft;

x = new double[6 * nBodies]; // create state variables

m = new double[nBodies];

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

m [i] = M / nBodies;

x [i * 6 + 0] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 1] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 2] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 3] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 4] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

x [i * 6 + 5] = Random.Range (-1.0f, 1.0f);

}

Init (6 * nBodies); // allocate Integrator work arrays

}

public override void RatesOfChange (double[] x, double[] xdot, double t)

{

// set xdot

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

xdot [i * 6 + 0] = x [i * 6 + 3];

xdot [i * 6 + 1] = x [i * 6 + 4];

xdot [i * 6 + 2] = x [i * 6 + 5];

}

// zero out vdot

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

xdot [i * 6 + 3] = 0;

xdot [i * 6 + 4] = 0;

xdot [i * 6 + 5] = 0;

}

// force terms

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

for (int j = i + 1; j < nBodies; j++) {

double dx = x [j * 6 + 0] - x [i * 6 + 0];

double dy = x [j * 6 + 1] - x [i * 6 + 1];

double dz = x [j * 6 + 2] - x [i * 6 + 2];

double dr2 = dx * dx + dy * dy +

dz * dz + soft*soft;

double dr = System.Math.Sqrt (dr2);

xdot [i * 6 + 3] += G * m [j] / dr2 * dx / dr;

xdot [i * 6 + 4] += G * m [j] / dr2 * dy / dr;

xdot [i * 6 + 5] += G * m [j] / dr2 * dz / dr;

xdot [j * 6 + 3] -= G * m [i] / dr2 * dx / dr;

xdot [j * 6 + 4] -= G * m [i] / dr2 * dy / dr;

xdot [j * 6 + 5] -= G * m [i] / dr2 * dz / dr;

}

}

}

}

In Model, add a public variable to the class so that it shows in the editor, and pass it to nBody through setIC.

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class Model : TimestepModel {

public float G = 1;

public float M = 10;

public float soft = 0.001f;

public int nBodies = 1000;

NBody nBody;

public GameObject bodyPRE;

GameObject [] bodies;

public override void TakeStep (float dt) {

nBody.RK4Step (nBody.x, modelT, dt);

}

// Use this for initialization

void Start () {

nBody = new NBody ();

nBody.setIC (nBodies, M, G, soft);

ModelStart ();

bodies = new GameObject[nBodies];

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

bodies [i] = Instantiate (bodyPRE);

}

}

// Update is called once per frame

void Update () {

for (int i = 0; i < nBodies; i++) {

Vector3 newPos = new Vector3 (

(float)nBody.x [i * 6 + 0],

(float)nBody.x [i * 6 + 1],

(float)nBody.x [i * 6 + 2]);

bodies [i].transform.position = newPos;

}

}

}

Run this for different values of soft. Notice that you tend to have fewer ejections using the softening factor. This isn’t always the case–sometimes close encounters, particularly three body encounters, really do result in ejections. The sue of the softening factor, however, should help to limit the number of these that are numerical artifacts.

Try cranking up N to something bigger, like 5,000. Save before running. Notice that the first step may take a substantial amount of time, but that with threading on you can still operate in the Unity editor. Save. Turn off threading. Save. Try to run again (be prepared to have to force quit the editor). Notice that you lose control over the editor while the steps are calculating. Try to press pause in order to regain control of the editor. If you can, quit the model. Turn threading back on. Save. If you can’t, force quit. Reopen the model. Turn threading back on. Save.

Play around with different values of N to see how this threaded version of the model has both better performance through threading at small N and better GUI control when calculating steps at large N.

(As I type this I am force-quitting Unity…)